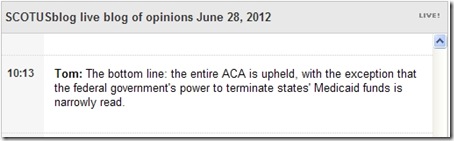

Yesterday was the most anticipated day at the U.S. Supreme Court in quite some time. The Court handed down its opinion in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, which decided the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act. And, Obamacare is alive and kicking. Here’s SCOTUSblog’s very tweetable summary of the historic opinion:

The key quote from the majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Roberts:

Our precedent demonstrates that Congress had the power to impose the exaction in §5000A under the taxing power, and that §5000A need not be read to do more than impose a tax. That is sufficient to sustain it.

In other words, the “mandate” to buy health insurance isn’t really a mandate at all, because individuals can simply refuse to buy health insurance and pay the resulting tax.

Here’s the entire 59-page opinion “in plain English,” again via SCOTUSblog (which gets huge props for its amazing live coverage):

If have a few spare moments and want to seek your teeth into the opinion, you can download all 187 pages here.

Or, you can read some summaries and commentaries from around the web:

- Health-Care Ruling: A Scorecard — from WSJ.com: Law Blog

- Don’t call it a mandate—it’s a tax — from SCOTUSblog

- What The Health Care Decision Means for Your Small Business — from WSJ.com: Small Business

- Supreme Court Upholds Individual Health Insurance Mandate — from SHRM

- Obamacare Decision: The Perils of Instant Analysis and Related Thoughts — from Michael Fox’s Jottings By An Employer’s Lawyer

- Social media angle on SCOTUS healtcare decision — from Internet Cases

- Ouch! CNN, Fox News Flub Coverage of Supreme Court’s Health Care Ruling — from TVLine

Here’s the rest of what I read this week:

Discrimination

- Say what? — from Walter Olson’s Overlawyered

- Is Breastfeeding Bias the EEOC’s Next Battleground? — from Employer Defense Law Blog

- Sticks and Stones Can Break Bones, but the Wrong Words Can Hurt Your Business — from Troutman Sanders HR Law Matters

- Banana-based racial harassment claim goes to trial — from Warren & Associates Blog

- Strippers Have Rights Too — from Donna Ballman’s Screw You Guys, I’m Going Home

- Fired for Reporting Workplace Injury — from The Proactive Employer Blog

Social Media & Workplace Technology

- Social Media in the Workplace: Much Ado about Nothing? — from i-Sight Investigation Software Blog

- Facebook Use At Work Falls, Twitter Is On The Rise — from The Huffington Post

- NBC Stations Keep Tabs On Employee Tweets — from TVNewsCheck

- What Not to Share: Enterprise Social Networking Etiquette — from The Up Mover

- ‘We Know What You’re Doing’ website outs drug users, boss-haters and more on Facebook — from BGR

- Is Your Co-worker Reading E-books On Company Time? — from Workplace Diva

- Employers Can Use Apps to Track Employees — But Is It a Good Idea? — from HR Hero’s Technology for HR Blog

- Pew survey finds that 17 percent of US cellphone users go online mostly on their phones — from Engadget Mobile

- Pinterest Legal Concerns: What is Lawful to Pin? — from Social Media Today

HR & Employee Relations

- Should you tell a job candidate about her body odor? — from Evil HR Lady, Suzanne Lucas

- Policies and User Adoption — from HR Examiner with John Sumser

- Workplace Investigation Pitfall: Failure to Use the Matter as an Opportunity to Improve the Organization and its Employee Relations Practices — from Strategic HR Lawyer

- Employer customer lists: "Whatever you say, dude." — from Eric Meyer’s The Employer Handbook Blog

- Legal Issues and Benefits to Employers for Employing Military Personnel — from Jason Shinn’s Michigan Employment Law Advisor

- Poll: Social Life, Not Social Media, Is Work's Biggest Distraction — from Workforce

- Employers to workers: Shape up, quit smoking — from Eve Tahmincioglu at Life Inc. on Today.com

Wage & Hour

- A work-life balance audit for employers — from Robin Shea’s Employment and Labor Insider

- Supreme Court To Decide Whether Employers Can “Moot” Collective Action — from Wage & Hour Tips

- SCOTUS Grants Cert in ERISA Case — from Phil Miles’s Lawffice Space

Labor Relations

- OMG! DUST NLRB Using Tech 2 Reach PPL re: PCA? UNTCO — from Dan Schwartz’s Connecticut Employment Law Blog

- 6th Circuit Holds Substantial Evidence Supports NLRB’s Conclusion That Charge Nurses Were Not Supervisors — from Wisconsin Employment & Labor Law Blog