Last week, SHRM released the results of its 3rd survey on Social Media in the Workplace [pdf]. SHRM polled 532 randomly selected HR professionals from its membership. According to the survey, 68% of companies use social media to communicate with external audiences (current customers, potential customers, or potential employees). Yet, only 27% provide their employees using social media any kind of training on its proper use.

This disconnect is disturbing. It’s bad enough that employees are using social media to communicate with each other absent any guidance or training. It’s astounding that nearly three-quarters of companies allow their employees to communicate with the public at-large in this manner.

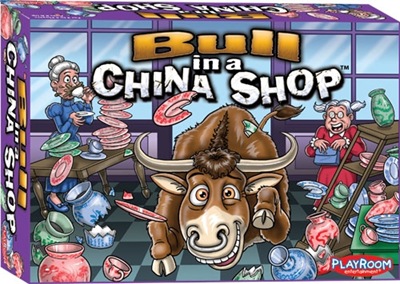

Without a policy establishing expectations for the proper use of social media internally and externally, this is what you are asking for in your business:

Please, for the love of god, do not allow anyone in your organization to use social media for any purpose without putting a policy in place and training your employees on that policy. Anything less is a recipe for a human resources or public relations disaster.

[Hat tip: Social Media Employment Law Blog]